Generalist Pests Inflict Greater Overall Damage, While Specialists Are More Lethal to Trees

Invasive Species and Forest Health: Unraveling the Complexities of Nonnative Pest Impacts on Trees Forests worldwide are critical ecosystems that support biodiversity, regulate climate, and provide numerous ecological services essential to maintaining planetary health. However, their stability is increasingly threatened by invasive pests, particularly nonnative insects that disrupt forest dynamics and cause widespread tree mortality. […]

Invasive Species and Forest Health: Unraveling the Complexities of Nonnative Pest Impacts on Trees

Forests worldwide are critical ecosystems that support biodiversity, regulate climate, and provide numerous ecological services essential to maintaining planetary health. However, their stability is increasingly threatened by invasive pests, particularly nonnative insects that disrupt forest dynamics and cause widespread tree mortality. A recent study published in the journal Forests sheds new light on the nuanced roles of nonnative specialist and generalist pests, offering novel insights into their patterns of damage and implications for forest management.

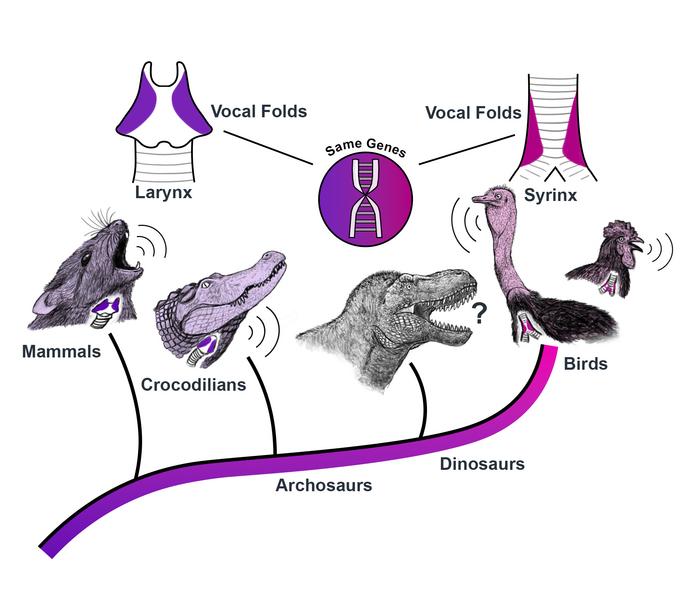

The research, led by Qinfeng Guo of the USDA Forest Service, underscores the urgency in categorizing invasive pests more accurately to optimize management strategies. These pests are traditionally divided into two groups: specialists, which attack a narrow range of host species, and generalists, which infest a broader spectrum of tree species across genera or families. At first glance, specialists appear more damaging because they focus their efforts on specific hosts, often leading to severe mortality in those populations. Conversely, generalists tend to spread nonlethal damage across multiple species, subtly weakening forest resilience over larger areas.

A case study central to the research is the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), a small aphid-like insect introduced accidentally to the United States in the 1950s. This pest exemplifies the devastating effects of invasive specialists. Native to East Asia and Japan, where natural predators and resistant host trees maintain population control, the adelgid has had catastrophic consequences for hemlock populations in the eastern U.S. Lacking these natural checks, it has caused mortality rates as high as 90% in some forest stands, dramatically transforming forest composition and threatening ecological stability.

The researchers analyzed 66 nonnative pest species, carefully comparing mortality and damage caused by specialists and generalists across the United States. Their approach included not only traditional binary classification but also a specialist-generalist continuum, which considers pest feeding behavior along a gradient rather than as discrete categories. This continuum approach enabled the team to capture more subtle variations in pest behavior and host responses, leading to clearer interpretations of infestation impact that binary classifications often obscure.

Their findings confirm that specialist pests are responsible for a higher incidence of tree mortality, exacerbating the loss of critical species in invaded habitats. This aligns with ecological theory, which predicts that host-specific pests exert concentrated pressure on limited hosts, eventually causing collapse in these populations if left unmanaged. However, the study also illuminates a less appreciated facet: generalist pests, while causing fewer fatalities per species, inflict widespread sublethal damage that can degrade forest health over time by reducing growth rates and increasing susceptibility to secondary stressors such as drought or disease.

Of particular note is the observation that the duration since a pest’s introduction inversely correlates with its current lethality. Older invasive pests tend to cause less acute mortality, possibly because the most vulnerable tree individuals have already been eliminated, infested areas have expanded, and host trees may have developed some degree of adaptive resistance. In contrast, newer invasives typically engage naive host populations, triggering more severe and rapid declines before management tactics can be effectively implemented.

The implications of these findings are profound for forest management and conservation. They stress the need for nuanced pest classification systems beyond the traditional specialist-generalist dichotomy, incorporating host range gradients and temporal dynamics of infestation impacts. Such refined classification facilitates targeted resource allocation, enabling managers to prioritize species and locations most at risk of rapid decline due to specialist pests while also monitoring and mitigating the insidious effects of generalists.

Moreover, Guo and Potter emphasize the critical gaps in current data, which hinder comprehensive assessments of pest impact severity and host vulnerability patterns. They advocate for expanded monitoring efforts, improved infestation databases, and interdisciplinary collaboration combining entomology, ecology, and forestry science. These efforts will enhance predictive models of invasion dynamics, guiding preemptive interventions before pest populations reach devastating thresholds.

The study also highlights the complex ecological interactions shaping pest-host dynamics. Invasive species often disrupt preexisting natural enemy relationships, such as predation and parasitism, which otherwise help maintain ecological balance in native ranges. The hemlock woolly adelgid’s unchecked proliferation in the eastern U.S. illustrates this phenomenon, where the absence of specialized predators allowed for explosive population growth and catastrophic forest damage. Understanding and potentially restoring these control mechanisms through biological control interventions remains a promising avenue but requires careful ecosystem impact evaluation.

Another challenge illuminated by the researchers is the difficulty in measuring and comparing the impacts of specialists versus generalists due to methodological inconsistencies across studies. Variables such as infestation intensity, host mortality, and sublethal effects often differ in their measurement and reporting standards, complicating efforts to synthesize data into usable guidelines. Standardized protocols for assessing insect damage and forest health metrics are necessary for advancing invasive species research and informing policy decisions.

In a broader context, the persistence and expansion of invasive forest pests underscore the pressing need for integrated pest management frameworks that acknowledge the inevitability of invasions. Human activities, including global trade and climate change, continue to facilitate the introduction and establishment of nonnative species, increasing the likelihood of new outbreaks. Adaptive strategies that combine early detection, rapid response, chemical and biological controls, and host resistance breeding will be essential in mitigating these threats and preserving forest ecosystem integrity.

Ultimately, Guo and Potter’s study contributes essential knowledge toward dissecting the multifaceted impact gradients of invasive forest pests. It challenges assumptions about pest behavior and damage patterns, advocating for a more sophisticated understanding of specialization and generalization in ecology. By reinforcing the value of gradient-based classifications and a holistic perspective on nonlethal damage, this research paves the way for more effective forest conservation strategies in the age of global biological invasions.

As the ecological and economic stakes rise, forest scientists, managers, and policymakers must heed these insights and bolster collaborative efforts to safeguard forest health. Although invasive pests are poised to remain persistent challenges, informed management grounded in rigorous scientific inquiry can mitigate their worst consequences and promote resilient forest landscapes for future generations.

Subject of Research:

Impact assessment and classification of nonnative specialist and generalist forest pests on tree mortality and damage in U.S. forests.

Article Title:

(This information is not provided in the content.)

News Publication Date:

(This information is not provided in the content.)

Web References:

https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/68905

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/hemlock-woolly-adelgid.htm

DOI link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/f16010127

References:

Guo, Q., & Potter, K. (Year). [Title of article]. Forests. DOI: 10.3390/f16010127 (Exact article title and year not provided.)

Image Credits:

Steven Katovich, Bugwood.org

Keywords:

Hemlock woolly adelgid, invasive species, nonnative pests, forest ecology, specialist pests, generalist pests, tree mortality, invasive insect management, pest classification, host resistance, biological control, forest health

Tags: categorizing invasive pests for better managementecological services provided by forestsforest health and biodiversitygeneralist vs specialist pestshemlock woolly adelgid effectsimpacts of nonnative insects on treesinvasive forest pestsmanagement strategies for invasive speciesnonnative species and forest dynamicsresilience of forest ecosystemsstrategies to combat invasive insect speciestree mortality caused by pests

What's Your Reaction?