STAT+: The new weight loss drugs are revolutionizing our understanding of desire. Food cravings could be just the beginning

Wegovy and similar drugs weren't originally designed to get into the brain. But scientists are learning that’s where they work to cause weight loss.

One month it was pizza. Starting in the late afternoon, while he was teaching a chem lab or grading student work, a part of Anthony Fernandez’s brain would stray to visions of steaming pies. The thought of sinking his teeth into one would tug at him as he packed up his things and walked to his car. By the time he pulled out of the Merrimack College campus, the urge would become a tractor beam, reeling him into the small shop just shy of Route 125 for a slice or three.

It would go on like that for weeks. Intrusive phantom wafts of bubbling hot cheese seeping into his psychic space. An unwelcome rush of saliva. A pizza-shaped itch begging to be scratched. Then suddenly they would be gone. Replaced by a new fixation: coconut jelly sticks from Heav’nly Donuts one month, Dunkin’s Beyond Sausage sandwich the next.

Fernandez knew it was these roving food obsessions that were losing him his latest weight loss battle. The 53-year-old chemistry professor had been hovering between 275 and 295 pounds for most of his adult life. At 5’10”, that made him obese by most body mass index calculations. Then during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, while much of the rest of the country struggled with the “quarantine 15,” Fernandez shed 20 pounds while hunkering at his Massachusetts home. When he lost easy access to fast food, the weight followed.

But as stores and restaurants began to open up again, the numbers on his scale crept steadily higher. So did the number of fatty acids and excess sugar in his blood. Around Thanksgiving 2021, Fernandez’s doctor approached him about trying something different: a new weight loss drug called Wegovy.

Originally developed for people with type 2 diabetes like Fernandez’s parents, Wegovy — the brand name for one of an expanding class of injectable medicines known as GLP-1 receptor agonists — was helping people lose up to 15% of their body weight. The needles initially made him hesitate. But by late February last year, Fernandez came around to the idea. The first time he tried Wegovy, he made his wife stand next to him just in case he fainted. But the pen hid the needle from sight and he barely felt it pierce his skin. By the end of that first month, his urges had evaporated.

“From the get-go, I stopped having a lot of those in-between meal cravings,” Fernandez said. “I don’t find that I need those snacks in the middle of the day or late at night. I used to need something after I put the kids to bed. I’d pull out a bag of carrots and a jar of hummus and eat the whole damn thing. I don’t do that anymore.”

Fernandez is among an exploding number of Americans taking these drugs for weight loss — more than 5 million people in the U.S. were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist in 2022, up from about 230,000 in 2019, according to a recent analysis by data insights company Komodo Health. Their rapid adoption is a testament to their striking effectiveness — unmatched by any weight loss drugs in history. But even scientists who’ve spent decades dissecting the actions of the gut hormone these medicines are designed to mimic have been surprised by their potency.

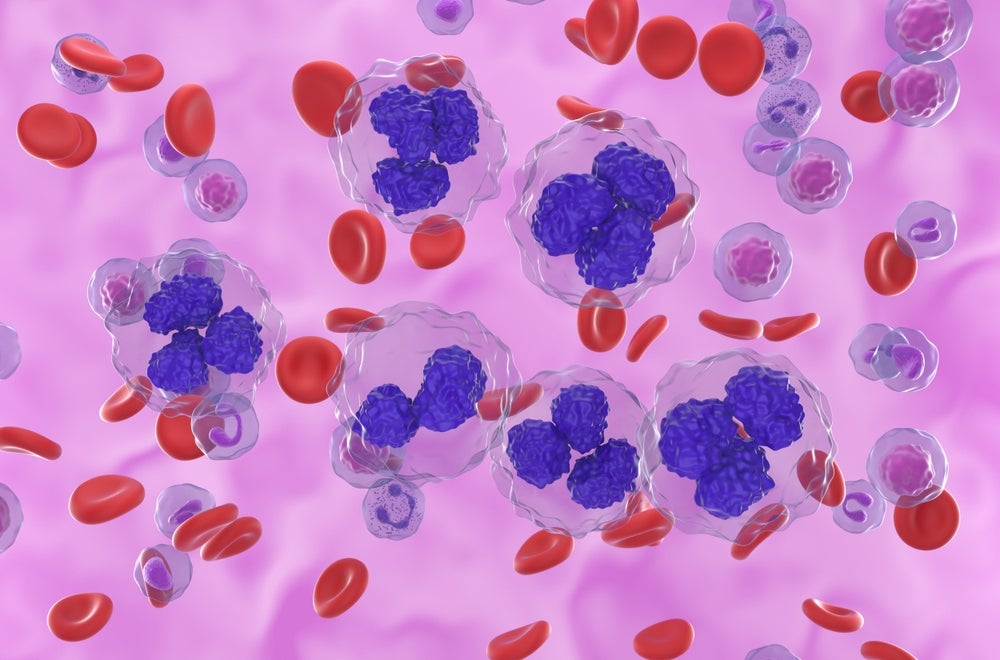

GLP-1 was first identified more than 40 years ago as a chemical messenger produced in the gut that tells the pancreas to crank out more insulin. Scientists learned pretty quickly that it does so by binding to GLP-1 receptors dotting the surface of beta cells in the pancreas. But only in recent years have researchers begun to understand the extent to which the brain also uses GLP-1 as a signaling molecule. It’s through networks of neurons coated with GLP-1 receptors that GLP-1 agonists act to suppress eating — not only, as was long believed, by communicating feelings of fullness, but also by altering circuits in the brain that drive desire.

This wasn’t obvious back when these drugs were beginning to be developed. They weren’t, originally, even designed to get into the brain. But more and more, scientists are learning that’s where they work to cause weight loss. These revelations have the potential to lead to more potent versions of these drugs in the future. They also raise an even more tantalizing question: If hormone hacking can erase food cravings, what other destructive desires might it liberate us from one day?

What's Your Reaction?