Critical minerals recovery from electronic waste

RICHLAND, Wash.—There’s some irony in the fact that devices that seem indispensable to modern life—mobile phones, personal computers, and anything battery-powered—depend entirely on minerals extracted from mining, one of the most ancient of human industries. Once their usefulness is spent, we typically return these objects to the Earth in landfills, by the millions. Credit: (Composite […]

RICHLAND, Wash.—There’s some irony in the fact that devices that seem indispensable to modern life—mobile phones, personal computers, and anything battery-powered—depend entirely on minerals extracted from mining, one of the most ancient of human industries. Once their usefulness is spent, we typically return these objects to the Earth in landfills, by the millions.

Credit: (Composite image by Melanie Hess-Robinson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)

RICHLAND, Wash.—There’s some irony in the fact that devices that seem indispensable to modern life—mobile phones, personal computers, and anything battery-powered—depend entirely on minerals extracted from mining, one of the most ancient of human industries. Once their usefulness is spent, we typically return these objects to the Earth in landfills, by the millions.

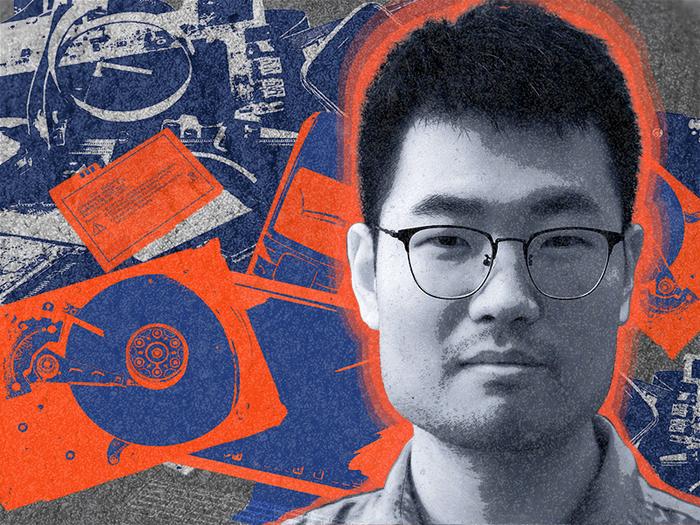

But what if we could “mine” electronic waste (e-waste), recovering the useful minerals contained within them, instead of throwing them away? A clever method of recovering valuable minerals from e-waste, developed by a research team at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, is showing promise to do just that. Materials separation scientist Qingpu Wang will present recent success in selectively recovering manganese, magnesium, dysprosium, and neodymium, minerals critical to modern electronics, at the 2024 Materials Research Society (MRS) Spring Meeting on April 25, 2024, in Seattle, WA.

Go with the flow

Just as a prism splits white light into a dazzling rainbow of colors based on distinct wavelengths, so too can metals be separated from one another using their individual properties. However, current separation methods are slow, as well as chemical- and energy-intensive. These barriers make the recovery of valuable minerals from e-waste streams economically unfeasible.

In contrast, the PNNL research team used a simple mixed-salt water-based solution and their knowledge of metal properties to separate valuable minerals in continuously flowing reaction chambers.

The method, detailed in two complementary research articles and presented this week, is based on the behavior of different metals when placed in a chemical reaction chamber where two different liquids flow together continuously. The research team exploited the tendency of metals to form solids at different rates over time to separate and purify them.

“Our goal is to develop an environmentally friendly and scalable separation process to recover valuable minerals from e-waste,” said Wang. “Here we showed that we can spatially separate and recover nearly pure rare earth elements without complex, expensive reagents or time-consuming processes.”

The research team, which included materials scientist Chinmayee Subban, who also holds a joint appointment with the University of Washington, first reported in February 2024 successfully separating two essential rare earth elements, neodymium and dysprosium, from a mixed liquid. The two separate and purified solids formed in the reaction chamber in 4 hours, versus the 30 hours typically needed for conventional separation methods. These two critical minerals are used to manufacture permanent magnets found in computer hard drives and wind turbines, among other uses. Until now, separating these two elements with very similar properties has been challenging. The ability to economically recover them from e-waste could open up a new market and source of these key minerals.

Recovering minerals from e-waste is not the only application for this separation technique. The research team is exploring the recovery of magnesium from sea water as well as from mining waste and salt lake brines.

“Next, we are modifying the design of our reactor to recover a larger amount of product efficiently,” added Wang.

Recovering manganese from simulated battery waste

Using a complementary technique, Wang and his colleague Elias Nakouzi, a PNNL materials scientist, showed that they can recover nearly pure manganese (>96%) from a solution that mimics dissolved lithium-ion battery waste. Battery-grade manganese is produced by a handful of companies globally and is used primarily in the cathode, or negative pole of the battery.

In this study, the research team used a gel-based system to separate the materials based on the different transport and reactivity rates of the metals in the sample.

“The beauty in this process is its simplicity,” Nakouzi said. “Rather than relying on high-cost or specialty materials, we pared things back to thinking about the basics of ion behavior. And that’s where we found inspiration.”

The team is expanding the scope of the research and will be scaling up the process through a new PNNL initiative, Non-Equilibrium Transport Driven Separations (NETS), which is developing environmentally friendly new separations to provide a robust, domestic supply chain of critical minerals and rare earth elements.

“We expect this approach to be broadly relevant to chemical separations from complex feed streams and diverse chemistries—enabling more sustainable materials extraction and processing,” said Nakouzi.

The research studies reported at MRS received support from a Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program and the NETS initiative at PNNL.

Learn more about materials sciences careers at PNNL.

Journal

RSC Sustainability

DOI

10.1039/D3SU00403A

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Flow-driven enhancement of neodymium and dysprosium separation from aqueous solutions

Article Publication Date

12-Feb-2024

What's Your Reaction?