Alzheimer’s disease progresses faster in people with Down syndrome

Nearly all adults with Down syndrome will develop evidence of Alzheimer’s disease by late middle age. A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that the disease both starts earlier and moves faster in people with Down syndrome, a finding that may have important implications for the treatment […]

Nearly all adults with Down syndrome will develop evidence of Alzheimer’s disease by late middle age. A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that the disease both starts earlier and moves faster in people with Down syndrome, a finding that may have important implications for the treatment and care of this vulnerable group of patients.

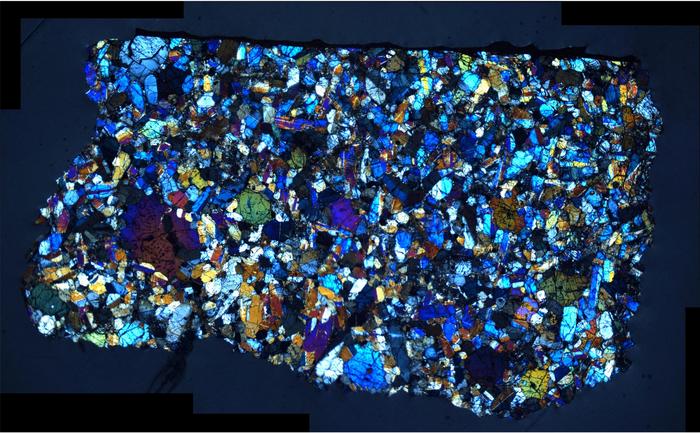

Credit: MATT MILLER/Washington University

Nearly all adults with Down syndrome will develop evidence of Alzheimer’s disease by late middle age. A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that the disease both starts earlier and moves faster in people with Down syndrome, a finding that may have important implications for the treatment and care of this vulnerable group of patients.

The findings were part of a study, available online in Lancet Neurology, comparing how Alzheimer’s develops and progresses in two genetic forms of the disease: a familial form known as autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease, and Down syndrome-linked Alzheimer’s.

“Currently, no Alzheimer’s therapies are available for people with Down syndrome,” said co-senior author Beau Ances, MD, PhD, the Daniel J. Brennan Professor of Neurology. Ances, who cares for patients with Down syndrome, explained that people with the developmental disability historically have been excluded from Alzheimer’s clinical trials.

“This is a tragedy because people with Down syndrome need these therapies as much as anyone,” Ances continued.

Down syndrome is caused by the presence of an extra chromosome 21. That extra chromosome carries a copy of the APP (amyloid precursor protein) gene, meaning that people with Down syndrome produce far more amyloid deposits in their brains than is typical. Amyloid accumulation is the first step in Alzheimer’s disease. For people with Down syndrome, cognitive decline often occurs by the time they reach their 50s.

People with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease also have a predictable timeline to cognitive decline. These patients inherit mutations in one of three specific genes: PSEN1, PSEN2 or APP. They tend to develop cognitive symptoms at the same age as did their parents: in their 50s, 40s or even 30s.

“Since these two populations develop disease at relatively young ages, they don’t have the age-associated changes seen in most Alzheimer’s patients, who are typically over age 65,” said corresponding author Julie Wisch, PhD, a senior neuroimaging engineer in Ances’ lab. “This, combined with the well-defined age of onset in both conditions, gives us a rare opportunity to separate out the effects of Alzheimer’s disease from normal aging and expand our understanding of disease pathology.”

As part of this study, the researchers mapped the development of tau tangles, the second step in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Using positron-emission tomography (PET) brain scans from 137 participants with Down syndrome and 49 with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s, the researchers examined when tau tangles appeared relative to amyloid plaques and which parts of the brain were affected.

The study revealed that amyloid plaques and tau tangles — protein abnormalities that precede cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s — accumulate in the same areas of the brain and in the same sequence in both groups, broadly speaking. However, the process happens earlier and more quickly in people with Down syndrome, and the levels of tau are greater for a given level of amyloid.

“Normal progression with Alzheimer’s is that you see amyloid, and then you get tau — and this happens five to seven years apart — and then neurodegeneration,” Wisch explained. “With Down syndrome, the amyloid and tau buildup happen at nearly the same time.”

There is currently only one treatment for Alzheimer’s disease approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and proven to change the course of the disease: lecanemab, which targets amyloid. Since amyloid accumulation is the first step in the disease, lecanemab is recommended for people in early stages of Alzheimer’s, with very mild or mild symptoms. Therapies targeting tau are also under development, aimed at people in later stages of the disease, when tau pathology plays a more prominent role.

“Since there is a compression of the amyloid and the tau phases of the disease for people with Down syndrome-associated Alzheimer’s, we will need to target both amyloid and tau,” Ances said. “We may need to come up with different approaches for this population.”

This paper is part of a collaboration between two major research consortia: the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN), an international network led by Washington University to study autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s; and the national Alzheimer’s Biomarker Consortium-Down Syndrome (ABC-DS), of which Washington University is a part. Ances leads a project within the ABC-DS to map the molecular changes that occur in the brain as Alzheimer’s develops in people with Down syndrome.

“This is the third paper that has come out of this longstanding collaboration between these two giant consortiums,” said co-senior author Brian A. Gordon, PhD, an assistant professor of radiology at Washington University’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology and an assistant professor of psychological & brain sciences. “By studying how Alzheimer’s develops in these two unique populations, we are building a more detailed and nuanced understanding of Alzheimer’s pathology that could lead to better diagnostics and therapies for people with any form of the disease.”

Journal

The Lancet Neurology

DOI

10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00084-X

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Comparison of tau spread in people with Down syndrome versus autosomal-dominal Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study.

Article Publication Date

15-Apr-2024

COI Statement

TLSB has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and Siemens; has a licensing agreement from Sora Neuroscience but receives no financial compensation; has received honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, or educational events from Biogen and Eisai Genetech; has served on a scientific advisory board for Biogen; holds a leadership role in other board, society, committee, or advocacy groups for the American Society for Neuroradiology (unpaid) and Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (unpaid); and has participated in radiopharmaceuticals and technology transfers with Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Cerveau, and LMI. EMD received support from the National Institute on Aging, an anonymous organisation, the GHR Foundation, the DIAN-TU Pharma Consortium, Eli Lilly, and F Hoffmann La-Roche; has received speaking fees from Eisai and Eli Lilly; and is on the data safety and monitoring board and advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Alector, and Alzamend. WS has received research funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. JPC serves as the chair of the American Neurological Association Dementia and Aging Special Interest Group and is on the medical advisory board of Humana Healthcare. CC has received consulting fees from GSK and Alector. AMF reports personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, Araclon/Grifols, and Diadem Research and grants from Biogen, outside the submitted work. BLH has received research funding from Roche and Autism Speaks; receives royalties from Oxford University Press for book publications; and is the chair of the data safety and monitoring board for the US Department of Defense-funded study Comparative Effectiveness of EIBI and MABA (NCT04078061). BTC receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health. EH receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the BrightFocus Foundation. FL is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging. HDR has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and is on the scientific advisory committee for the Hereditary Disease Foundation. J-HL has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. RJP receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. RJB is Director of DIAN-TU and Principal Investigator of DIAN-TU001; receives research support from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, DIAN-TU trial pharmaceutical partners (Eli Lilly, F Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Eisai, Biogen, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals), the Alzheimer’s Association, the GHR Foundation, an anonymous organisation, the DIAN-TU Pharma Consortium (active members Biogen, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and F Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech; previous members AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Forum, Mithridion, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and United Neuroscience), the NfL Consortium (F Hoffmann-La Roche, Biogen, AbbVie, and Bristol Myers Squibb), and the Tau SILK Consortium (Eli Lilly, Biogen, and AbbVie); has been an invited speaker and consultant for AC Immune, F Hoffmann-La Roche, the Korean Dementia Association, the American Neurological Association, and Janssen; has been a consultant for Amgen, F Hoffmann-La Roche, and Eisai; and has submitted the US non-provisional patent application named Methods for Measuring the Metabolism of CNS Derived Biomolecules In Vivo (13/005,233 [RJB and DH]) and a provisional patent application named Plasma Based Methods for Detecting CNS Amyloid Deposition (PCT/UC2018/030518 [VO and RJB]). BMA receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and has a patent (Markers of Neurotoxicity in CAR T Patients). MSR has received consulting fees from AC Immune, Embic, and Keystone Bio and has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Avid, Baxter, Eisai, Elan, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, and Roche. JHR has received funding from the Korea Dementia Research Project through the Korea Dementia Research Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and the Ministry of Science and ICT, South Korea (HU21C0066). All other authors declare no competing interests.

What's Your Reaction?